II. Pods vs DaemonSets

This tutorial focuses on the different options available when setting up Linkerd. You will learn about the differences between using Pods or DaemonSets when running in Kubernetes.

A service mesh for Kubernetes

As a service mesh, Linkerd is designed to be run alongside application code, managing and monitoring inter-service communication, including performing service discovery, retries, load-balancing, and protocol upgrades.

At a first glance, this sounds like a perfect fit for a sidecar deployment in Kubernetes. After all, one of Kubernetes’s defining characteristics is its pod model. Deploying as a sidecar is conceptually simple, has clear failure semantics, and we’ve spent a lot of time optimizing Linkerd for this use case.

However, the sidecar model also has a downside: deploying per pod means that resource costs scale per pod. If your services are lightweight and you run many instances, like Monzo (who built an entire bank on top of Linkerd and Kubernetes), then the cost of using sidecars can be quite high.

We can reduce this resource cost by deploying Linkerd per host rather than per pod. This allows resource consumption to scale per host, which is typically a significantly slower-growing metric than pod count. And, happily, Kubernetes provides DaemonSets for this very purpose.

Deploying Linkerd per host requires more configuration when using DaemonSets. This tutorial shows you how to configure the service mesh for per-host deployments in Kubernetes.

Architecture options

One of the defining characteristics of a service mesh is its ability to decouple application communication from transport communication. For example, if services A and B speak HTTP, the service mesh may convert that to HTTPS across the wire, without the application being aware. The service mesh may also be doing connection pooling, admission control, or other transport-layer features, also in a way that’s transparent to the application.

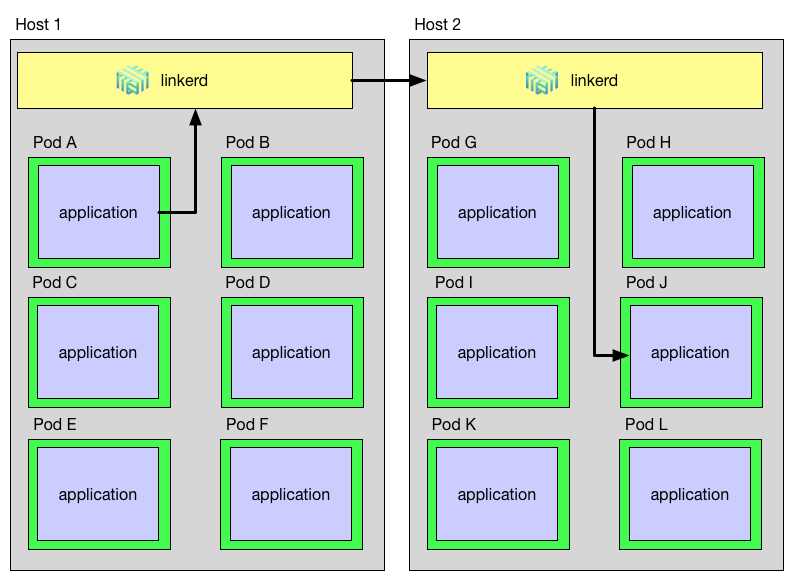

In order to fully accomplish this, Linkerd must be on the sending side and the receiving side of each request, proxying to and from local instances. E.g. for HTTP to HTTPS upgrades, Linkerd must be able to both initiate and terminate TLS. In a DaemonSet world, a request path through Linkerd looks like the diagram below:

As you can see, a request that starts in Pod A on Host 1 and is destined for Pod J on Host 2 must go through Pod A’s host-local Linkerd instance, then to Host 2’s Linkerd instance, and finally to Pod J. This path introduces three problems that Linkerd must address:

- How does an application identify its host-local Linkerd?

- How does Linkerd route an outgoing request to the destination’s Linkerd?

- How does Linkerd route an incoming request to the destination application?

What follows are the technical details on how we solve these three problems. If you just want to get Linkerd working with Kubernetes DaemonSets, see part one!

Identify the host-local Linkerd

Since DaemonSets use a Kubernetes hostPort, we know that Linkerd is running on

a fixed port on the host’s IP. Thus, in order to send a request to the Linkerd

process on the same machine that it’s running on, we need to determine the IP

address of its host.

In Kubernetes 1.4 and later, this information is directly available through the Downward API. Here is an except from hello-world.yml that shows how the node name can be passed into the application:

env:

- name: NODE_NAME

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: spec.nodeName

- name: http_proxy

value: $(NODE_NAME):4140

args:

- "-addr=:7777"

- "-text=Hello"

- "-target=world"

(Note that this example sets the http_proxy environment variable to direct all

HTTP calls through the host-local Linkerd instance. While this approach works

with most HTTP applications, non-HTTP applications will need to do something

different.)

In Kubernetes releases prior to 1.4, this information is still available, but in

a less direct way. We provide a simple script

that queries the Kubernetes API to get the host IP; the output of this script

can be consumed by the application, or used to build an http_proxy environment

variable as in the example above.

Here is an excerpt from hello-world-legacy.yml that shows how the host IP can be passed into the application:

env:

- name: POD_NAME

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.name

- name: NS

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.namespace

command:

- "/bin/sh"

- "-c"

- "http_proxy=`hostIP.sh`:4140 helloworld -addr=:7777 -text=Hello -target=world"

Note that the hostIP.sh script requires that the pod’s name and namespace be

set as environment variables in the pod.

Route an outgoing request to the destination’s Linkerd

In our service mesh deployment, outgoing requests should not be sent directly to the destination application, but instead should be sent to the Linkerd running on that application’s host. To do this, we can take advantage of powerful new feature introduced in Linkerd 0.8.0 called transformers, which can do arbitrary post-processing on the destination addresses that Linkerd routes to. In this case, we can use the DaemonSet transformer to automatically replace destination addresses with the address of a DaemonSet pod running on the destination’s host. For example, this outgoing router Linkerd config sends all requests to the incoming port of the Linkerd running on the same host as the destination app:

routers:

- protocol: http

label: outgoing

interpreter:

kind: default

transformers:

- kind: io.l5d.k8s.daemonset

namespace: default

port: incoming

service: l5d

...

Route an incoming request to the destination application

When a request finally arrives at the destination pod’s Linkerd instance, it

must be correctly routed to the pod itself. To do this we use the localnode

transformer to limit routing to only pods running on the current host. Example

Linkerd config:

routers:

- protocol: http

label: incoming

interpreter:

kind: default

transformers:

- kind: io.l5d.k8s.localnode

...

Conclusion

Deploying Linkerd as a Kubernetes DaemonSet gives us the best of both worlds—it allows us to accomplish the full set of goals of a service mesh (such as transparent TLS, protocol upgrades, latency-aware load balancing, etc), while scaling Linkerd instances per host rather than per pod.

For a full, working example, see the part one, or download our example app. And for help with this configuration or anything else about Linkerd, feel free to drop into our very active Slack or post a topic on Linkerd discourse.